Chances are, we are part of the 99,9% — just ordinary people, trudging through our mostly uneventful existence. Shure, life has its moments; a baby born, a mother lost, a night to remember. But it is in the quiet, everyday happenings our lives unfold. The small dramas of being alive. The chill down the spine when the phone rings and it says “No Caller ID”, the epic quest to find matching socks, the rosy shade of a child’s sticky kiss on your cheek. In a sense, we’re all the NPC’s, non-playable characters, in a grand RPG (role-playing game) where some hero is off to some grand adventure somewhere else. And then there’s us, going about our day, getting coffee on our way to work, wondering if our houseplants are silently judging us.

Yet, when you look out the car window, the landscape sweeping by, we add a soundtrack to the scenery. When your heart is broken, you wait for the rain to fall as if on cue. And when you for the 5th time start a gym membership you see a mental montage take you from sad sack to god-tier athlete in 30 seconds flat. We don’t just live, we produce, direct, and star in our own personal Hollywood epic, acting as the main characters in the retelling of our lives. And maybe we need to be, maybe it’s the only thing we can do.

Vonnegut’s Story Shapes and the Arcs We Construct

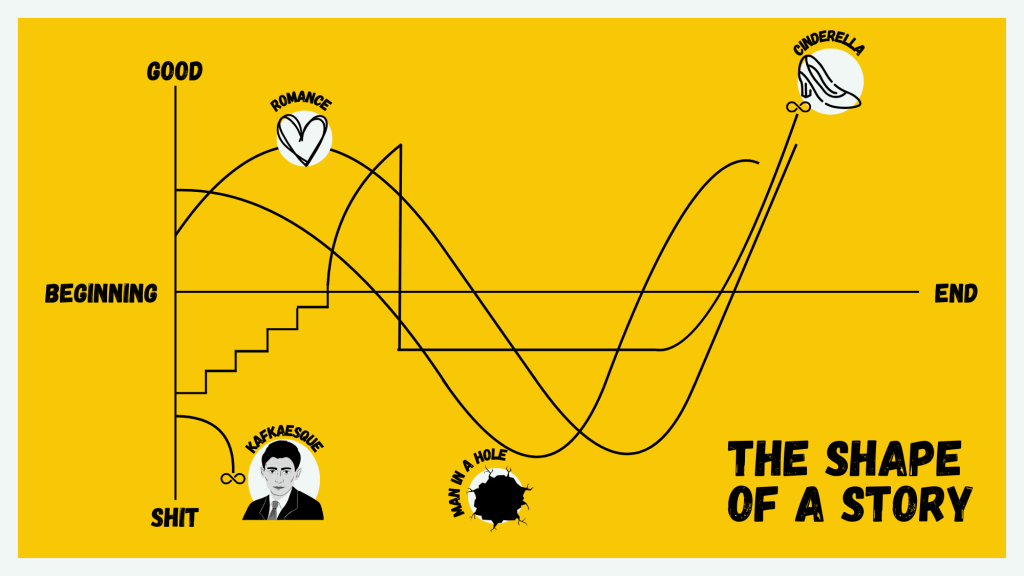

In his famous four-minute explanation of the shape of a story, Kurt Vonnegut explained four storylines that we are particularly fond of. First, he plots the y-axis; good vs ill fortune. The x-axis is simple, just the “beginning” and “ending”.

In Vonnegut’s first example, Man in a Hole, the main character, the titular man, is happy. Then the unforeseen happens and he trips into a pit of existential despair. When he ultimately crawls out he’s stronger, wiser, and possibly with a book deal. Second, we have The Romance. Things are good. Love makes things great. Tragedy happens. Love triumphs. Roll credits.

The grandest story, however, is Cinderella. The poor, lonely girl has lost her mother and is now in the throws of a wicked stepmother. Along comes the fairy godmother and inch by inch, our girl is transformed from soot-covered nobody to Bell of the ball. Then by the strike of twelve, she’s back in her miserable life. At least until the prince recognises her and sweeps her away to neverending bliss.

Or our story can be kafkaesque, starting with ill fortune and then an infinity of misery. But what our stories cannot be is a continuation of the same, good and bad intertwining without a clear arc. Like life.

Narrating Ourselves Into Meaning

So we construct these kinds of arcs in our lives.

“I thought we were happy, but then she left me without warning, and I descended into a spiral of Netflix and ice cream. But therapy saved me, and now I’m dating someone objectively superior.”

Or: “I was doing well at work, a little bored, but then—bam!—I got sacked, spent months surviving on microwave popcorn, and now, behold, my multi-billion-euro empire.”.

Life must mean something. Otherwise, it’s just… happening.

According to philosophy PhD Grace Hibshman, we do it because narrating our lives helps us zoom out. We become the audience of our own story, watching from a distance, nodding along to the plot beats. And from that vantage point, things make more sense.

Philosopher Mark Schroder on the other hand, argues that we aren’t just telling stories, we are our stories. In the article “Narrative and Personal Identity,” Schroder explains his narrative theory of identity, arguing that the key to our identities is defined by the best and most coherent story possible of our lives. Our understanding of ourselves is fluid and context-sensitive.

Sartre and the Radical Freedom to Rewrite Ourselves

If we accept that who we are is a story, then who’s writing it? French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre would argue that we are. And if who we are can be defined through narrative, then we have a choice in how we define that narrative.

Sartre calls this radical freedom: the ability to define ourselves beyond our circumstances. If we don’t, we act in bad faith (mauvaise foi), deceiving ourselves into thinking we are stuck in a role given to us, rather than acknowledging we have the power to change. We become stock characters: “the good girl,” “the rebel,” “the misunderstood genius,” “the perpetual underdog.” We take on the role of the main character, the one around which everything revolves.

Making a spectacle of the self

In her article “Main Character Syndrome,” Anna Gotlib, an associate professor of philosophy at Brooklyn College in New York, warns that when we see ourselves as the star of the show, it’s easy to treat everyone else like NPCs, objects on our path to glory. But there’s another aspect to this. The main character isn’t free. They’re stuck in their arc, trapped in a script designed for easy consumption—something neatly packaged and streamlined, an identity that performs well for an audience.

In Society of the Spectacle, Guy Debord argues that modern life is no longer about being, but about appearing. Identity isn’t something you are, it’s something you perform. In this scenario, we don’t tell stories to understand ourselves but to be seen. Debord warns us that the pressure to be an image, an aesthetically pleasing, narratively satisfying version of ourselves, can be so overwhelming that we forget how to simply live.

So what happens when we stop telling stories for meaning and start telling them for validation? When we stop defining the self and start performing it?

The loss of meaning and rise of optimisation

Humans are relational beings. We tell stories to connect, empathise, and create meaning. In her research on “experience-taking,” psychologist Lisa Libby has found that when we step into a story, we don’t just understand someone’s perspective, we become them for a moment. The story dissolves our isolation and bridges the gap between experience and understanding.

So the problem is not that we want to tell stories, but when stories become performances something shifts. We go from sense-making to transaction. Your personal narrative is now a social currency with the possibility to make or break you. Instead of connection, we get self-optimisation. The question subtly shifts from:

✔️ “What does this story mean to me?”

❌ “How will this story be received?”

This is Debord’s spectacle in action: the moment when we become more concerned with appearing interesting than by actually being. Our story becomes less about truth and more about presentation, designed for audience approval.

This is the Cinderella Story, the Man in a Hole, and the Hero’s Journey — clean, compelling, and shareable. But also, fundamentally, a performance. Here, Sartre’s concept of bad faith resurfaces. When we start performing our narrative, conforming to the expectations of what a “good” story should be, we risk trapping ourselves in a role that doesn’t fit. We become characters in a spectacle, partly of our own making, mistaking the story for the self.

Embracing the ordinary in search of truth

Life is full of loose ends, unresolved tension, and moments that don’t mean anything at all. The most profound experiences often don’t fit into neat arcs—they simply happen, and then they pass. Maybe there is an underlying need to turn them into a story for us to create meaning. But let that story be rich and complex. Or in the words of Virginia Wolf: “I am not one and simple, but complex and many.”

To embrace the ordinary is to step outside the spectacle and exist without the constant need to conform. It means:

- Allowing joy to be small and unremarkable.

- Letting pain exist without demanding an immediate lesson.

- Living without an audience in mind.

Freedom lies in the choices we can control. And we can control for what purpose we shape the stories about ourselves. Make it count. Because maybe the real challenge isn’t telling a better story, but a true one.